Road, Railways and Bridges

The lines of communication in any area represent the answers found by man to the questions posed by nature – crossing mountains, bridging rivers, providing social and economic links between people. This article by Hilda Hesling, Braeval, Daviot, describes some of the transport links in the Strathnairn area, and explores both how these form a response to historical development, and also themselves create further changes.

Moving with the Times

By Hilda Hesling, Daviot

The three Historical Accounts, written by the ministers of the time, provide us with some information on Strathnairn itself, and on a handful of landed families, but are largely silent on details of the lives of the great majority of those who lived here. Archaeological remains, in particular the footings of many 'hut circles' clustered in small settlements, show that the Strath has supported a considerable population since the Bronze Age, if not earlier. Stone ruins and the remains of old field systems from the eighteenth century provide evidence of more recent habitation. The lack of physical remains of dwellings in the intervening millenia is probably due to the fact that the houses of the common people were made of turf and wood, material that has decayed entirely. Documentary evidence from as far back as the thirteenth century does exist showing that portions of the Strath were gifted or conveyed, proving that the land, and the people living on it, with a status at that time almost of serfs, had indeed some value. Details of the lives of the people are almost non-existent until patchy marriage and baptismal records dating from the early eighteenth century are examined, or glimpses gleaned from legal documents or from town or presbytery records from Inverness. Much more information comes to light once Census records are available, and vital records (births, marriages, deaths) become compulsory; but this does not happen until well into the nineteenth century. They do show a society where almost all of the families were of Clan Chattan origin, with most of them taking their living from the land. We can safely assume that people lived here much as they did all over the Highlands: largely self-sufficient in food, fuel, and shelter, many crofters had a second, or even third skill: that of shoemaker, or tailor, or slater for example, and much seasonal work was done as a community, ensuring that crops could be harvested, or cultivation done, to the rhythm of the seasons and the weather.

Few Strathnairn folk would have travelled far from home, although the Rev Gordon, in 1796, does record the departure of many of the young for seasonal work in southern Scotland, lamenting the return of these 'partial emigrants' in autumn 'to live with their parents or relations during the winter upon the common stock of the family.' These young people would have travelled on foot by some of the rough tracks over the mountains, and ran considerable risks doing so. As economic migrants, however 'partial' they no doubt did contribute to the family's income. Cash incomes were also generated from the sale in Inverness of loads of peats or other produce in season. Access was by simple tracks over the Drumossie Muir, or the Leys Brae; to visit kinsfolk and friends in the other straths lying to the south and west, Strathdearn and Stratherrick, they took rough paths through the hills. One road which has remained much the same still exists: the single track road from Farr to Garbole, winding over the hills, following the lie of the land, only the line of huge electricity pylons reminding one of the present day; otherwise this road is substantially the same one as the drove road which linked the fertile areas of the Black Isle, Easter Ross and the Aird, passing across the river Ness at the eastern end of Loch Ness at Bona, crossing Strathnairn at Farr, passing through the hills to the cattle markets of the south. This route is marked on one of the earliest detailed maps of the area: that done for the York Timber Company in 1729. Strathnairn is described on this map as 'barren land,thirteen miles long and three broad.' The York Timber Company was at pains to record all valuable woods, and we can assume from this that none existed at that time in Strathnairn.

Other, wilder, episodes of cattle rustling are well documented; at one time Strathnairn folk were afraid to leave their homes for fear of raiders, who would swoop down on the peaceful strath and make off over the hill tracks with animals and other booty, leading to blood shed on more than one occasion. In 1676, a visit from the Inverness Presbytery had to be delayed as the Daviot and Dunlichity elders were obliged to ‘abyd in the Glens to shelter and keep ther bestiall and goods from the Lochaber and Glencoa Robers.’ Just as their houses were built of material to hand, so were roads and bridges: on a visit in 1770, Bishop Forbes records a bridge at Tordarroch made of the trunks of ‘immense trees, dug out of the moss’ - all that was left of the immense forests that had once covered the whole area. On the road to Killin, leading into the hills from Stratherrick is a beautifully made, and quite intact, clapper bridge over a mountain burn: several conduits made of stone, over-topped with large slabs. This bridge has only quite recently been replaced by a modern structure, and the old bridge remains, the small patch of road providing a convenient parking spot. The name ‘clapper’ is thought to refer to the sound of the water rushing through the stone conduits; when the hill burns are in full spate, the Killin bridge illustrates this perfectly.

A mid-Victorian watercolour shows the detailed structure of the old wooden bridge over the Craggie Burn; perched high up on the rocks, it consisted of long split trunks, underpinned with wooden buttresses; the stone walls on either bank which formed the foundation can still be seen from the later stone bridge just upstream. These simple wooden bridges could not withstand some of the violent deluges, but if damaged, were easily and quickly repaired. This bridge was the replacement of the one mentioned in D. Nairne's accounts of 'Memorable Highland Floods'. The effects of the disastrous floods of 1829 are recorded thus: 'The rain in the upper part [of Strathnairn] began on Sunday evening, the 2nd August, and continued with little or no intermission till Tuesday, the 4th. The Nairn, and the other streams, rushed from the mountains, filled with gravel and stones, and committed great havoc on many farms especially on that of Mains of Aberarder, where seven hands were able to reap in one day all that remained of a crop for which £150 of rent was payable. The fulling mill at Faillie was the sport of both floods: the first carried a huge, heavy mass of machinery down to Cantray, nine miles below, whence it was, with much labour, brought back to its Highland home, but it was hardly well established there, when the flood of the 27th bore it away on a second expedition, and landed it at Kilravock, after a voyage of eleven miles. Two bridges were carried away on the Parliamentary line of road; one at Dunmaglass, and the other - of two arches - over the burn of Aultrough, which joins the Nairn from the right. At Craggy, the Inn of that name, standing very picturesquely, and apparently beyond all danger, on the top of a green alluvial bank, amongst irregularly dropped birches, and surrounded by birch-covered knolls, formed, with its bridge below, a very beautiful scene. But the flood of the 27th carried away the bridge, cut the bank into a high perpendicular precifice, and was only prevented from undermining and bringing down the inn by the accidental fall of a tree, which turned the force of the torrent. The mill of Clava, on the right bank, was destroyed by the first flood and was re-built and repaired exactly in time to be again demolished by the second.'

After the failed rising of 1715, the thoughts of the Hanoverian government had turned to taming the Highlands; after all, the Catholic son of the last Stuart king still provided an ever present reminder of the threat of revolution and civil war, and the Highlands, still largely ‘uncivilized’ were considered the ideal launch-pad for such a venture. Accordingly, it was decided prudent to establish armed garrisons, and to build a road system to facilitate the movement of soldiers and supplies. A soldier, General Wade, was put in charge of the construction and Edmund Burt was his surveyor. Burt wrote in 1728 to the Mackintosh: ‘I doubt not you have long since heard of General Wade’s intention to make a good road from Inverness to Blair by the way of Drumochter…I think the way over the Ford of Faillie will be the best, in regard the rocky steep hill and the bog of Daviot will be very expensive and the hill in particular hardly capable to be made good for wheel carriage...I beg of you that you will please to give of your countenance to the workmen and order your people to furnish them in the best manner they can, with provisions and necessarys. They are to begin as soon as the weather will permit.’ A road was accordingly built which left Inverness and crossed the River Nairn at Faillie, eventually reaching the barracks at Ruthven, near Kingussie. Another Wade road linked Inverness with the garrison at Fort Augustus passing through Stratherrick. These old roads can still be walked in many places, and fragments of the old bridges can be seen near the quarry at Midlairgs in Daviot. The present single-track stone arch at Faillie is a later replacement, but the original bridge at Whitebridge in Stratherrick still stands. Wade’s roads soon fell into disrepair; travellers in the eighteenth century were resigned to frequent delays; Lord Lovat, travelling to Edinburgh, took a wheelwright with him to repair the coach: the journey still lasted more than a week.

After the second Stuart rising which failed so dismally at Culloden in 1746, measures taken by the government meant the unravelling of the clan system as it had existed for centuries. Some clan chiefs, to curry favour and to speed up the return of their forfeited estates raised regiments to fight in the colonial wars being waged by a country establishing an Empire overseas. Simon Fraser, son of the Lord Lovat who had been executed for his part in the Jacobite rising of 1745, was one of these, and many men from Stratherrick and upper Strathnairn fought with Fraser’s Highlanders in the Seven Years War in America and stayed on to exploit the riches of continental America. Simon Fraser, in due course, had his estates returned and after the United States achieved independence, many Scottish former soldiers made their way to Canada, and entered the Canadian fur trade: Simon MacTavish from Stratherrick and his nephew William MacGillivray from Dunmaglass, were major players in the North West Company which ran the trade for many years; Fort William, on the Great Lakes, being named after the latter. Other Strathnairn men, Shaws and Mackintoshes, also became fur traders. Many Strathnairn folk left and made solid livings overseas, their names recorded only on the burial stones of graveyards in places as far apart as Nova Scotia and New Zealand, part of the vast Highland diaspora at a time when starvation was only one poor season away.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the situation in the northern Highlands and Islands, where poverty was rife, and the numbers of those who emigrated were rising steeply, was sufficiently serious to warrant a Royal Commission, which led to major improvements in what we would now call the infrastructure; a new system of roads, funded partly by the government and consequently known as Parliamentary roads, was established and the huge engineering undertaking of the Caledonian Canal planned, partly to improve communication, but also to provide employment. From now on, the construction by Governments of good roads and bridges assumed an economic and social dimension, and was no longer simply a military necessity. The Parliamentary road which crossed Strathnairn at Daviot deviated substantially from the earlier Wade road, and follows the line we see today as far south as the Nairn, now renamed the ‘old road’ as it climbs the Craggie Brae, winds past Loch a Chorain and crosses the plain of Moy. Tolls were paid at various points on the road, and older residents of Daviot remember 'Toll Cottage' at the foot of the Craggie Brae.

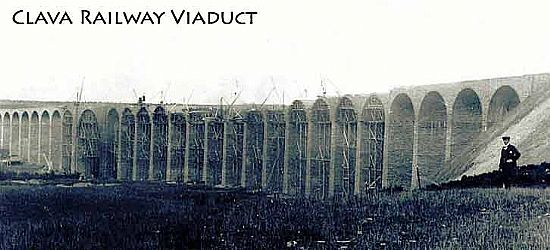

These roads, being better built than the old ‘Wade’ roads, provided much needed employment to many locals, who could, at slack times on the farms, break stones and repair the roads as paid employment, not, as previously, as unpaid work forming part of a tenancy. A new road also meant that people living in the Daviot area had much easier access to Inverness, enabling them to take full advantage of the opportunities presented later in the nineteenth century, when the establishment of new schools after the Education Act of 1872 meant a standard public network of primary schools replacing the old parish schools. Bright pupils could now much more easily finish secondary education in Inverness. By the 1880s post offices were established at Daviot, Farr and Aberarder; the mail being taken to Daviot and then on to the other offices by pony and trap. With the main road south passing over Strathnairn, and railway fever raging in Victorian Britain, it was only a matter of time before the railway came also, and in 1898 the Highland Railway was opened, providing a straight route from Carrbridge to Inverness, a journey previously only possible by train taking the long loop through Grantown, Elgin and Forres. The line crossed the Nairn at Clava by means of a magnificent viaduct, one of the longest in the country. The construction of the line, like the Canal before it, provided much work for local people, and many bright youngsters were guided into the offices of the Highland Railway to work as accountants and administrators. Crofters living along the line soon became accustomed to the new phenomenon, and often benefited from a few loads of coal offloaded at strategic points by a friendly fireman. Local people often took the train from Daviot to Inverness for their shopping, and one lady who lived close to the line two miles from Daviot station, would fling bags of messages out of the slow-moving train near her home on the return journey, thus walking home from the station unencumbered.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the lands which in earlier times had been in the ownership of a small number of families belonging to various septs of Clan Chattan, were formed in much of the upper part of the Strath into large estates, and as time went on, financial necessity meant that these went to owners who ran them primarily as sporting estates, with home farms, and many local people providing the services of gamekeepers, ghillies, stalkers, beaters etc, the women working in domestic service. Photographs from one such, at Dunmaglass, record life in the 1890s.

The first half of the twentieth century brought little change to the rhythm of life in Strathnairn. Mail would be delivered by postmen on bicycles, children walked to school on roads still largely free of traffic. At Daviot, in the summer months, the children attending the school crossed the river on stepping stones, avoiding the long detour by road; though they were strictly warned to keep away from the river during the winter! Most farm work was done by horses until the Second World War; the blacksmith would cycle out from Inverness to shoe these gentle giants. Village halls were built and used by local WRI, drama groups, literary societies; the Strathnairn Farmers Association organized annual ploughing, sheepshearing and hoeing matches and an annual show and sale of produce. We can look back now with nostalgia, but life was always hard in an upland strath. Depopulation continued, and after the Second World War many of the farms, hewn a century before from heather moors, were now sold for afforestration.

The 1970s brought yet another phase to the continuing cycle of route-making across the Strath. Increasing volumes of road traffic, and a decline in the use of the railway, meant that the need for improvements to the main road south was becoming urgent. The new route which was decided on combined the line of the Wade road from Moy to the Nairn, and then the line of the Parliamentary road from the river through Daviot and on to Inverness. Many surveyors worked (and much money was spent) on the initial surveys - a far cry from Edmund Burt’s one-man team in 1728! Work continued for some time, and now forms our own new ‘gateway to the Highlands.’ The close of the twentieth century has brought about yet another phase in the loops and spirals of Highland history. Once the dual carriageway through Daviot was completed, pressure for housing became intense, and many new houses have been built here, and also in the upper parts of Strathnairn. People began once again to appreciate the benefits of country living, this time combined with ever-improving access to jobs and leisure facilities in the growing town - eventually to become the city - of Inverness. Once again roads and bridges have been improved throughout the Strath to cope with increased traffic, and whilst the schools at Clava and Brin have both closed, those at Farr and Daviot remain, the latter mounting stiff opposition to a proposed closure in 1997. This was an instance where improved access to Inverness was cited as a reason for transporting pupils to an urban primary school, but a strong case was made for the retention of the school as a focal point within a rural community, and this view prevailed. Good schools, a strong community council, the building of two village halls, one a replacement at Daviot, and the other a new hall at Farr, new traditions established - an annual Gala at Farr - and a thriving Feis, where youngsters are taught traditional Highland music-making, all show that this is a community in good heart, with involvement of old and young alike.

HISTORY OF ROADS IN STRATHNAIRN

The Inverfarigaig Road - One of Thomas Telfords Parliamentary Roads

By Tim Rose

It is likely that there has always been a road of some form along Strathnairn as it is an obvious route following the river and bounded by high ground on either side. When Timothy Pont was surveying ca. 1600 it appears that he travelled down the length of the Nairn on the South side of the river and back up on the North[1] side suggesting that there were routes on both sides of the river. It is, however, into the 18th century before we get documentary evidence of a road along Strathnairn.

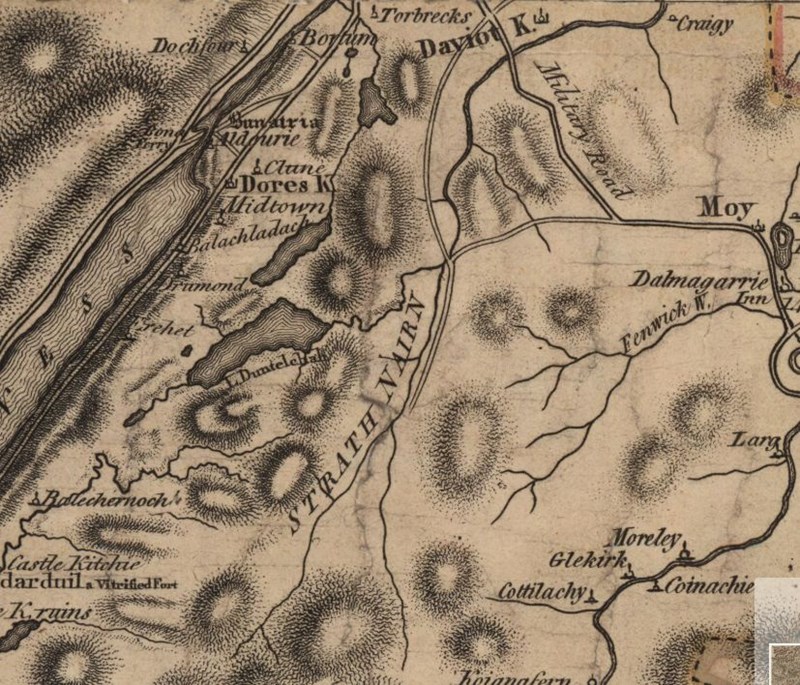

The 1789 map by John Ainslie[2] (below) shows a road heading up Strathnairn, one branch of which starts at a junction with the military road just north of Failie bridge and probably corresponds to the current road along the North side of the Strath. Although there are errors on the map it is most likely that the road crosses the river on the current Tordarroch bridge (the current stone bridge was built in 1781[3]), indeed the 1848 revision of this map identifies the bridge as being at Tordarroch.[4]

The other branch comes from a junction with the military road between Daviot and Moy.

A sketch made by Lord Lovat (thought to be early 1800s) shows the road from the Tordarroch bridge joining the military road at Creag an Eoin[5].

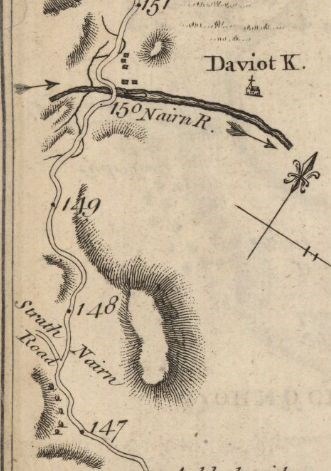

This road is also marked on Taylor and Skinner's road atlas[6] (1776) which helpfully has mile markers which tell us that the junction was around 2.5 miles from the river Nairn at the summit of the road (NH 729 346) (click on grid reference to see map), from here the main road went down through Wester Lairgs farm to come out at the current B851.

By 1813 Ainslie was showing the new parliamentary road as well as the old county road.[7]

Much of this section of original county road likely fell into disuse from around 1810 when the newly opened parliamentary roads provided a better alternative; however, if you can see through the modern forestry which has hidden it, traces of it can still be found.

It starts around 200m North of the monument to the Rout to Moy and the initial stages are difficult to follow through the modern forestry although the route is clearly marked on modern maps. A short distance along the county road, from the junction with the military road, is the Uaigh an Duine-Bheo[8].

Original county road marked with red dots.[9]

Looking West along the old county road from NH720 348. Wester Lairgs is just beyond the trees. Photo T Rose.

Ainslie's 1789 map probably depicts roads which are capable of carrying wheeled traffic, Bishop Forbes describes driving a chaise (a 2 wheeled carriage) from Inverness to Tordarroch on the 27th June 1770 and then the wooden bridge that preceded the current stone bridge at Tordarroch (built in 1781) was described by bishop Forbes in 1770 as “..a wooden bridge of large trees, digged out of a moss, by which horses and wheeled machines do easily cross the water.”[10]

Although Forbes did not continue in his chaise it would be logical for the road to be suitable for wheeled vehicles all the way to where it joins the military road as depicted on Taylor and Skinners atlas. Indeed this route, from Craig an Eoin to Inverness via Tordarroch was probably the original road in and out of Strathnairn for vehicular traffic.

Attempts appear to have been made in the 1770s and 1780s to improve the roads to and within Strathnairn and in 1781 the Commissioners of supply in Inverness allocated £15 to “the Stratherrick road” including building a bridge over the river Brin[11] - it is unlikely that they would be building a bridge over a river without a road leading to and from it. Indeed Bishop Forbes had abandoned his chaise at Tordarroch before heading further up the Strath “as there is not yet a chaise road any further in Strathnairn that Tordarroch, tho’ it is apon the advancing” [12]

The Parliamentary “Inverfarigaig Road”

The Scottish Highland Roads and Bridges act of 1803 established the Commissioners for Roads and Bridges in the Highland of Scotland[13] on the 4th of July, within weeks they had received a petition requesting a road through Strathnairn.

The convenor of Inverness-shire has transmitted to us the minutes of a general meeting of that county , holden on 16th August last, at which (among other things) it was resolved “that a line of road from Inverfarigag through Strathnairn and Strathearn to Craigoin should be recommended to our notice” as a road of great expected utility in that country. We have accordingly given directions for a survey and estimate thereof.[14]

The commissioners appointed James Donaldson to undertake a survey of the line of the road. James Donaldson was a military surveyor who had recently been working on improving the road through the Slochd[15] and had previously been encountered by Thomas Telford when Telford had conducted his survey of the Highlands in 1802. Telford had recommended to the government committee that Donaldson was someone who should be knowledgeable about Highland roads however in their report it was stated;

The committee, averting to Mr Telfords suggestion of an examination of Mr Donaldson, called him before them; but found that he had never travelled any part of the country from Fort Augustus, Westward, to Bernera or the Lochs, and that his information was solely, as to that part of the country, derived from others.[16]

The impression is that the examination ended fairly quickly once this lack of experience was revealed however, it does appear that Donaldson was soon able to broaden his horizons westward as he was jointly responsible for surveying the road to Loch Hourn and the road to Loch-na-gaul (Arisaig) in 1803/4.

Donaldson submitted his survey in June 1804. However, he had deviated from the instructions he had been given to terminate the road at Craigoin[17] and planned it to go to Faillie instead, this caused some dispute and in the end Thomas Telford was called to visit the strath and give his opinion[18]. Telford concluded that the original plan to terminate the road at Craigoin was the best option and so the plans were altered. Further delays (see below) meant that when the Moy road was surveyed in 1805 the Inverfarigaig road still hadn’t been started and so the North end of the road was altered again to re-route and extend it to meet the Moy road at the current location near the war memorial. This meant changing the plans back to something very similar to Donaldson’s original plan.

The South end of the road had been planned to meet the military road at Inverfarigaig bridge however the Caledonian Canal included plans for a pier at Inverfarigaig and so the plans for the road were extended to meet the pier.[19]

As the plans changed the opportunity was taken to replace James Donaldson as surveyor with William Cumming. Experience was starting to show that Donaldsons cost estimates (and he had surveyed all of the early parliamentary roads) were significantly below actually costs[20] which was causing a lot of hardship for contractors who had taken on contracts at a price which guaranteed they would lose money and difficulties for the commission who had to deal with projects struggling as the contractors had gone bankrupt. It is hardly surprising that, in the early years of the commission, mistakes were made as neither this type of competitive tendering for contracts or road building on this scale was something that anyone had experience of. The delays resulted in it taking 4 years for the Inverfarigaig road to go from conception to contract signed were probably a blessing in disguise as it allowed hard lessons learned on other contracts to be applied to this one.

Survey costs inevitably mounted up;

James Donaldson was paid £40 15s 0d for the original survey.[21]

William Cumming was paid £61 19s 3d for updating the original survey.[22]

William Cumming was paid a further £10 10s 10d for making adjustments to the ends on the road.[23]

This total surveying cost (£113 4s 13d) was not insignificant when you consider that, in 1830 the Littlemill bridge was rebuilt for around £150[24].

Further delays were encountered due to the number of proprietors involved and the need to agree to the assessment of what proportion of the cost each proprietor would pay (proprietors were responsible for funding 50% of the road and the government would fund the other 50%[25].) In the end agreement was found and the following heritors agreed to pay for 50% of the cost of the road;

The honourable Colonel Archibald Fraser, of Lovat

John MacIntosh, esquire, of Aberarder.

John Lachlan M’Gillivray, esquire, of Dunmaglass.

James MacIntosh, esquire, of Farr.

Simon Fraser, esquire, of Foyers.

Simon Fraser, Esquire, of Farraline

Thomas Fraser, esquire, of Gortuleg.

Alexander Fraser, esquire, of Dell.

Doctor William Mac Inen Fraser, of Balnain.

The right honourable Lord Woodhouslee.

Thomas Gilzean, esquire, of Bunachton.

Captain Donald M’Queen, of Corrybrough and

Ludovik M’Bean, esquire, of Tomatin[26]

The contract for constructing the road was duly advertised and in October 1807 was awarded to John Campbell, Donald Campbell (road builders) and Malcolm Macpherson (stonemason) all from Rothiemurchus. These contractors were financially backed by John Peter Grant Esq of Rothiemurchus, Angus Edward farmer at (Kerrocomeanach), John Macpherson farmer at Dalchully, William Mitchell farmer at Gordon Hall, Donald Macnab farmer at Laggan, John Macnab and Ronald Macdonald both farmers at (Gallavie)[27]. This backing was required as it was a fixed price contract and the commission needed to know that the resources were available to finish the road in the case that it went over budget or the contractors went bankrupt. The project was scheduled to be completed by Martinmass 1810.

Work commenced at the Inverfarigaig end of the road and initially appeared to progress relatively well.

In October 1807 Malcolm Macpherson, John and Donald Campbell, entered into contract to complete the Inverfarigaig road at Martinmass 1810, and the work hitherto performed by them excels in quality that on any other road, but the progress has been not such that as to afford much expectation of completion within the time appointed. In length only one fourth of the road, mostly at the west end, is finished; but as the most rugged part has been first executed, one third of the road making has been supposed to have been accomplished; but very few of the bridges are yet built.[28]

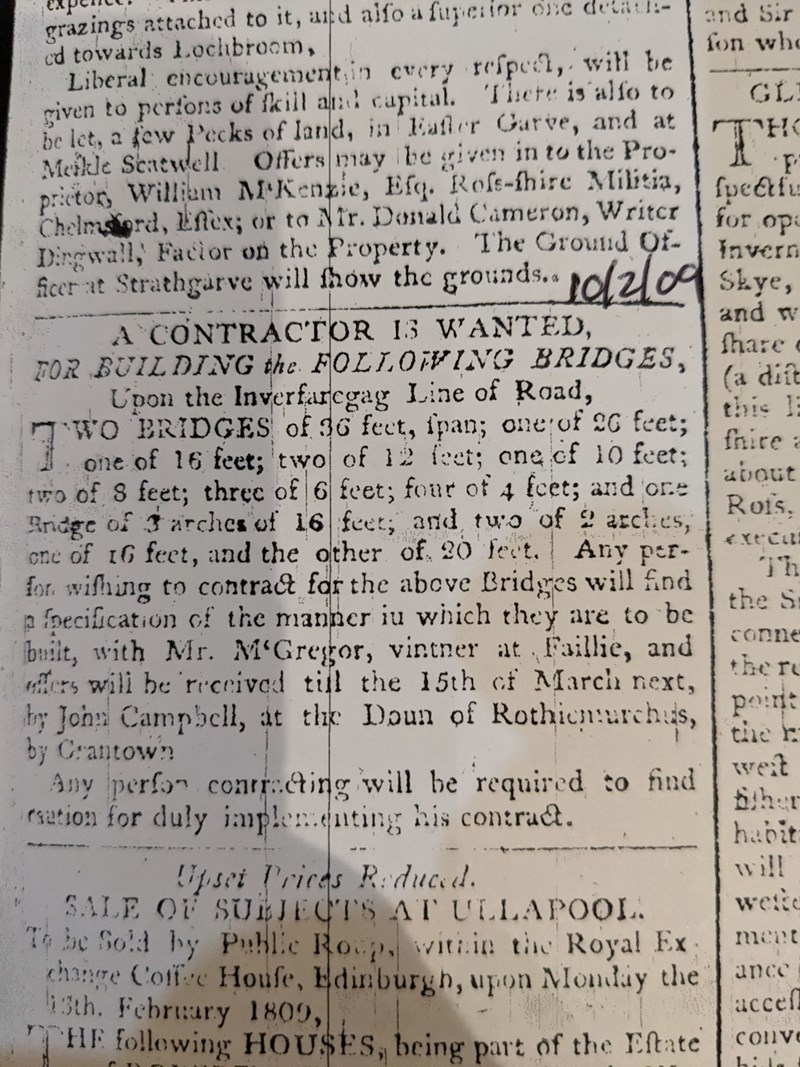

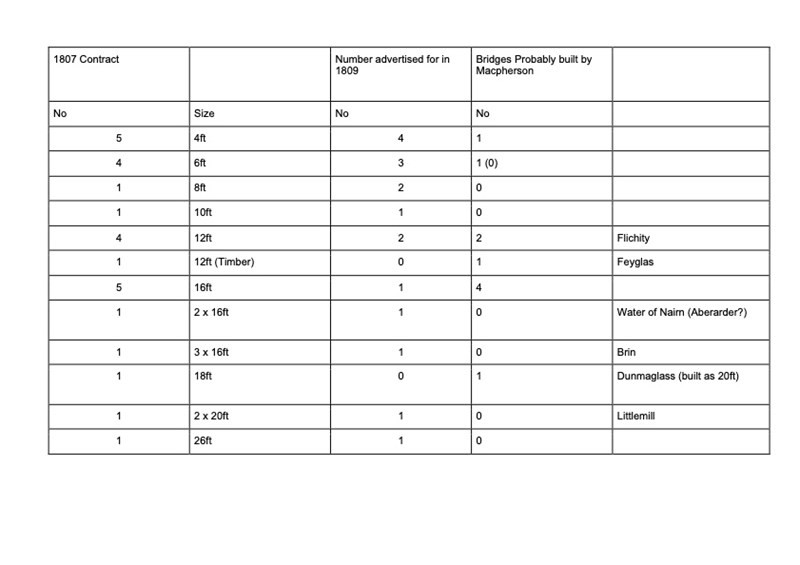

The comment about bridges is significant and it does appear that Malcolm Macpherson was struggling with the bridge building. In February 1809 John Campbell was advertising in the Inverness Journal looking for sub contractors to build some of the bridges for him.[29] It can be assumed that the role of the stonemason was critical to the success of the project as there were 28 stone bridges to be built. It may be significant to note that it is John Campbell and not Malcolm Macpherson that is advertising for this work.

Comparing the list of bridges specified in the contract[30] with the list of bridges being advertised shows that only a few of the smaller bridges had been completed by February 1809. The largest bridge that we assume Macpherson built (the 18ft bridge at Dunmaglass) unfortunately collapsed in 1829 which does not leave an encouraging impression!

(note that the bridge spans specified in the contract were a minimum and so contractors may have occasionally built larger bridges, if site conditions required it or it was more convenient for them. This may explain the discrepancies in the above table).

Further problems were encountered in 1809 when the 36ft bridge over the Nairn at Farr collapsed whilst it was under construction[31], as this was one of the bridges put out for tender it is not known who the builder was.

The 1811 report has a slightly different tone to it;

The Inverfarigaig road has been conducted by the contractors in an unexceptional manner from its commencement, and a final inspection was requested by them in terms of the contract in November last: but at the request of some of the neighbouring proprietors, they consented to postpone it till the present spring, thereby taking apon themselves indirectly the repairs consequent apon the intermediate winter season. We did not think it equitable to insist upon this, and the voluntary acquiescence of the contractors was the more commendable as it is known that they have not been gainers by their contract. The inspection has now actually taken place, and in the opinion of the neighbouring heritors and of our superintendent, the contract has been satisfactorily fulfilled, and the retained one eighth part of the price is consequently now payable to the contractors.[32]

It appears that progress on the road had significantly speeded up. In the 18 months from the start of the contract to April 1809 they had completed around a third of the road and very few bridges, however, in the following 18 months they had completed enough to request the final inspection required for handing over the road at completion. However, this increase in speed (probably due to bringing in sub contractors to build the bridges) does seem to have affected the quality of the work. “Unexceptional” is a noticeable step down from the “excels in quality” used to describe them in 1809.

The 1813 report gives a few clues about Campbell, Campbell and MacPhersons business and reveals that they made a loss. It is not known if they were able to cover the loss themselves or if their surety were required to pay for the completion of the road ;

The Inverfarigaig road bordering on Loch Ness, which was finished at the date of our last report (in April 1811), cost the public and the contributors about four thousand five hundred pounds, and (we are sorry to say) something further was expended by the contractors, who appear to have made an improvident offer, not allowing for accidents and contingencies.[33]

Contractors were responsible for any damage to the road up until the point it was handed over after final inspection and so the collapse of the bridge of the Nairn at Farr, that we know happened during construction in 1809, would have been their financial responsibility. Whether this accident was what made it a loss making contract or whether there were other accidents as well is not known.

Campbell, Campbell and Macpherson won the contract with a bid of £4128[34] and so that is what they were paid. The total cost of the road was slightly higher by the time surveying costs and the expense of additional bulwarks and a short section of additional road at Sockich was included.

The Branch Road

The route of the Inverfarigaig road follows the route of the current B851 through Strathnairn however there is evidence that the original road included a branch road that is no longer in existence.

The 2nd report describes the road;

with a small branch Westwards near Tordarroch[35]

Where was this road and what do we know about it? In order to head West from the main road a bridge would have been required to cross the river Nairn. There are a number of mentions of this in the records but perhaps the most illuminating is in a letter written by two of the local proprietors to Mr Rickman (of the Parliamentary Roads Commission).

“We regret that the communication from the south to the north of the river Nairn near the march between Farr and Flichity has not been placed in a situation of more general utility to make an easier and shorter access from the Inverfarigaig road on the south side of the river to the county road on the north side leading to the 2 churches and the burial grounds and the town of inverness. At the same time we are satisfied that the circumstances which led the surveyor to choose the situation was its being a better foundation and some rock on each side and would be attended with less expense than a more useful situation for the benefit of the county and if a bridge shall be continued there and rebuilt, as the former one, before completely finished, fell down last year, we beg leave to observe that the approach to it is so difficult by natural obstacles that the bridge will be totally useless unless the honourable board will be please to make a proper road thereto. We understand that the Mr Cumming who surveyed and planned the bridge which fell down stated that a sum of £30 should be given in aid to the district to make the roads of approach to this bridge”[36]

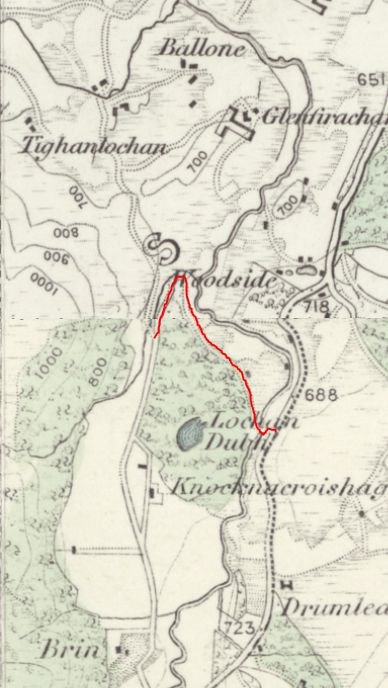

This letter reveals 1) The purpose of the road (to improve access to the road on the North of the strath and therefore churches and Inverness), and 2) the location (between Farr and Flichity).

The above map[37] from 1866-1870 shows the existence of a bridge over the Nairn at Sockich (underneath the h of Lochan). This is confirmed to be our bridge as we know that a parliamentary bridge was built at Farr with a 36ft span[38] and the bridge abutments can still be found at Sockich. They measure 36ft between them.

Bridge abutment and approach road at Sockich, looking South. Photo T.Rose.

Quite why the Parliamentary Roads Commission had approved a bridge to be built without a suitable approach road is difficult to understand but it does appear to be the case. It is likely that the approach road requested in the above letter corresponds to the short stretch between the current B851 and the river - this goes down a steep slope which would be very difficult to traverse without the construction of a raised road. As the contract was very specific as to the specification and dimensions of the road perhaps this short section was accidentally omitted from the scope of works allowing the contractor to avoid responsibility for it.

The reports of the Roads Commission record the application for this short approach

Mr MacIntosh of Aberarder and, and Mr Fraser of Foyers, have since applied for a small branch road of approach to Nairn Bridge[39]

This approach was approved and built (as can be seen by remains at the location). The contract for this was awarded to Alexander and Foyers for £36.[40] Such a small contract being awarded to a different contractor and not Campbell, Campbell and Macpherson who were onsite building the infrastructure either side of this bit of road appears to be a little strange. Perhaps this reflects the rigorous way in which the commission put even the smallest job out to competitive tender or, perhaps, reflects a loss of confidence in the main contractor.

With the purpose of this branch road being to link up with the county road on the North of the strath the parliamentary road was extended to the North to join with the pre-existing road from Brin to Dunlichity (marked red on the above map). Note that this goes around a small hill, something that the surveyors would have insisted on in order to make the road suitable for heavy wheeled vehicles. This road is still visible.

Branch road just prior to its junction with the Brin road. Note that the fence runs along the surface of the road so the road is wider than it first appears. Photo T. Rose

There is no record (that I can find) of when the bridge disappeared and the road was abandoned however some assumptions can be made.

1) The parliamentary roads commission published meticulous records and they do not mention this bridge collapsing. The commission ended in 1863 and so the bridge was probably still standing then.

2) The 1st series 1in OS map, which was surveyed between 1866 and 1870 shows the bridge in place.[41]

3) The 1st series 6in OS map, which was surveyed in 1871, shows the bridge missing.[42]

It is possible then, that the bridge collapsed sometime between 1866 and 1871. There was a significant flood on the 31st January 1868[43] that partially destroyed the bridge in Nairn town. No mention is made of our bridge at Sockich but could this have been the night it was destroyed?

There are oral accounts locally that report that the bridge collapsed at the time a funeral procession was crossing it. There are also accounts that someone died when the bridge collapsed although it is not clear if this was in 1809 when it collapsed whilst under construction or at a later date when the bridge collapsed at the end of its life. If you know any more about this then please get in touch.

To get an idea of what the bridge at Sockich would have looked like, consider the larger of the bridges at Dunmaglass which is the same span (36ft) and would have been built to the same design and probably by the same people as the bridge at Sockich.

Bridge at Dunmaglass. Photo T. Rose

The 1829 Flood and Maintenance

The Parliamentary commission quickly realised that, without maintenance, roads quickly fell into disrepair, sometimes to the point of becoming unusable. A robust system of maintenance was therefore organised. Contracts were awarded to maintain the roads. On some roads this was funded by tolls however, the decision to impose tolls on a road was usually made if there was sufficient traffic to make the toll collection worthwhile. Many Highland roads, therefore, did not have tolls and so were maintained from a government grant that was administered by the parliamentary commission. The Inverfarigaig road fell into this category and no tolls were ever imposed on it.

Maintenance contracts only covered routine wear and tear and catastrophic acts of God were covered by the commission directly.

…agreements have since been made with experienced persons, at moderate prices, for keeping each road respectively, and the bridges in repair for 1 year. The contractor in those agreements, of course does not undertake to uphold the bridges against accidents; nor is he answerable for breaches in the parapets, breastworks, or retaining walls, should such breaches in any case exceed twenty cubic yards.[44]

The commission could respond rapidly to catastrophic events and John and Joseph Mitchell (the superintendents on the ground) occasionally had to traverse the country in the worst weather to organise repairs to critical infrastructure. Although it is unrelated to our account of the Inverfarigaig road it is instructive to see how the Commission could respond in an emergency.

On the 13th January 1818 a large flood washed around 4000 birch trees (which had been felled and were waiting to be transported) down the river Morriston which destroyed the Torgoyle bridge. Word reached John Mitchell in Dunkeld on the 20th January and, after a dangerous journey through a snow storm that covered the road 6 to 12ft deep in places he reached Inverness on the 25th January. It then took a further 5 days to visit the site and return to Inverness from where he gave directions for the preparation and purchase of materials.

Materials were accordingly collected, and a hard frost having reduced the quantity of water in the river Morrison, Mr Mitchell went to Torgoyle on the 25th February, and in the course of the next 4 days, constructed 6 piers, formed of 4 piles each. These were driven into the bed of the river, by means of a piling engine, which with its supporting scaffold, was to be moved for every pile; an operation that kept the workmen for hours together in the river, at that time four feet deep. This was no small effort in a sharp frost; but there was no alternative, and the timber bridge was rendered passable in the beginning of March, and completed at an expense of £167.[45]

In 1824 when John Mitchell died at the age of 45 it is not surprising that many considered the hardships he encountered in his work to have contributed to his early death. There are no records from the workers who spent 4 days chest deep in icy water but there are other accounts of just how hard work on the roads could be. [46]

The largest flood to have affected the river Nairn in recorded history appears to have been in August 1829. This is extensively documented in a contemporary book - The Great Floods of August 1829 in Moray by Sir Thomas Dick Lauder (1830) and depicted by Edwin Landseer (no doubt with some artistic license) in his painting Flood In The Highlands.

Flood in the highlands by Edwin Landseer - On display in Aberdeen art gallery.

The 1829 flood destroyed the smaller (20ft) bridge at Dunmaglass and most of the Littlemill bridge (then known as Redburn or Aullt Ruaidh[47]) as well as a small bridge at Tearnoch near Farr[48]. The latter was immediately repaired at ‘trifling expense’ and practicable fords were made at the other 2 locations. As traffic on the road was not heavy, temporary fords were made whilst tenders were requested for rebuilding the bridges. The contract was won by John Davidson of Inverness who rebuilt both bridges for a total of £220.[49] (As both bridges were 20ft arches the timber formwork used to support the masonry as it was being built would have been able to be re-used on both bridges. As formwork typically accounted for 10% of the cost of a bridge having both bridges in the same contract would make the project more cost efficient.) Interestingly John Davidsons was not the lowest bid suggesting that the commissioners were more concerned about quality of work than saving a few pounds on the contract.[50]

The Problem of the Rivers

There are repeated mentions in the records about the risk posed by rivers in Strathnairn shifting their course and undermining roads and bridges. This appears to be a particular feature of the rivers in the upper Nairn catchment as similar emphasis is not found in the Parliamentary roads reports of other areas

Having learned that certain water courses, which have been diverted from the natural channel, may hereafter desert the intended bridges on this line of road, unless the artificial banks and bulwarks are maintained, we have applied to the proprietors, through the county meeting of Inverness-shire, to give security to this effect but we have not yet received their answer.[51]

The difficulty of confining the waters to those channels over which some of the bridges on this road have been thrown still remains, and may perhaps render the county or the proprietors liable to occasional expense hereafter.[52]

Mr MacIntosh of Aberarder and, and Mr Fraser of Foyers, have since applied for a small branch road of approach to Nairn Bridge; also for bulwarks to confine the rivers in the line of this road (especially the Nairn) within the proper channels, for the safety of the new bridges. The estimate amounted to about two hundred pounds, and seeing the propriety of incurring this moderate expense, we readily consented to their request; and Mr MacIntosh of Aberarder has since finished bulwarks in a satisfactory manner for the present; whether the irregular current of the rivers is effectually restrained, time can only demonstrate.[53]

….contract requires bulwarks to be built 10 yards upstream and down from bridges to ensure river is constrained under the bridge. On the bridges over the Nairn and the Brin (or Brinach) this is not sufficient to keep the rivers in their channel. In every spate these rivers spread out endangering the bridges and destroying the road. Suggestion that the bulwarks are extended considerably and make them more substantial. The surrounding land appears lower than the present bed of the river.[54]

The river is to be cleared of gravel for 70 yards upstream of the bridge for 16 yards in breadth and to a depth of 3ft.[55]

The Nairn, and the other streams of the valley, rushed from the mountains, filled with gravel and stones, and committed great havoc on many farms, especially on that of Mains of Aberarder…..[56]

Readers familiar with the area, even over 200 years later, may find some of these comments and warnings still relevant today. The bed of the river Brin is significantly higher than the surrounding land and still threatens the road every time there is a significant flood (although the modern bridge appears much less vulnerable). The Nairn at Aberarder was was also “highly dynamic……perched above its floodplain”[57], although significantly altered in 2017.

The Road Today

Through Strathnairn much of the road has been upgraded since it was first built although it still follows the same line and many original features can still be seen. The last original bridge in Strathnairn was the Flichity bridge which was removed in 2024. The 1830 bridge at Littlemill (Redburn) still stands in good condition although it ceased to be used in 2014.

Much of the section through the Pass of Inverfarigaig is in near original condition with the road still its original width and most of the bridges are original.

That so much of the original road is still used as the main road through Strathnairn (and indeed, so much of the modern road network in the highlands continues to be the roads built in the period 1803 to 1816) is testament to the planning, labour and foresight of the Parliamentary road builders.

“We should deem ourselves to be bad stewards of the public expenditure did we not labour for posterity as well as for the present generations”[58]

Notes on Sources:

The commissioners for roads and bridges kept meticulous records and published regular reports although, somewhat confusingly, there are 2 series of reports.

1) “Reports of the Commissioners for Roads and Bridges in the Highlands of Scotland”. These were published bi-annually from 1804 to 1821.

2) “Reports of the Commissioners for repair of roads and bridges in Scotland”. These were published annually from 1815 to the commission's dissolution in 1862.

The change in report reflects the change in emphasis of the commission as construction of new roads largely stopped in 1816.

For a good overview of the Parliamentary roads see “New Ways Through The Glens” by A.R.B Haldene. 1973.

Joseph Mitchell (Inspector of Highland Roads and Bridges from 1824 to 1867) published his memoirs which contain a lot of information about his work. “Reminiscences of My Life In The Highlands”. 1883/1884 (2 vols).

[1] https://maps.nls.uk/pont/texts/transcripts/ponttext127v-128r.html

[2] https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400648

[3] Authors research, see forthcoming article.

[4] https://maps.nls.uk/view/216441383

[5] National Records of Scotland, RHP8908

[6] https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400375

[7] https://maps.nls.uk/view/216442052

[8] https://her.highland.gov.uk/monument/MHG30203 (the map on this page shows the road much clearer than it actually appears on the ground)

[9]https://www.google.com/maps/place/Inverness,+UK/@57.3859531,-4.1463819,2318m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m6!3m5!1s0x488f715b2d17de2b:0x624309d12e3ec43d!8m2!3d57.477773!4d-4.224721!16zL20vMDEyZDlo!5m1!1e4?entry=ttu

[10] Craven (ed), 1886. Journals of the Episcopal Visitations of the Right Rev Robert Forbes. P287/8.

[11] Minutes of the Commissioners of Supply, Highland Archive Centre HCA/CI/1/1/2

[12] Craven (ed), 1886. Journals of the Episcopal Visitations of the Right Rev Robert Forbes. P288.

[13] See A.R.B Haldene. New Ways Through The Glens for background to the Parliamentary Roads.

[14] 1st Report, p14, 1804.

[15] https://nosasblog.wordpress.com/2016/08/31/the-military-roads-from-slochd-to-sluggan/

[16] 1802, 23rd December. Minute of the committee of the Directors of the Highland Society of Scotland, appendix to A Survey and Report of the Coasts and Central Highlands of Scotland by Thomas Telford, p27

[17] Craigoin is Creag an Eoin, a hill on the southwest side of the Stairsneach nan Gaidheal. Routing the road to here would have meant following the old road marked on Ainslie’s map and meeting the current B851 near the Farr Hall.

https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.8&lat=57.38153&lon=-4.11187&layers=257&b=1&o=100

[18] 2nd Report, p11, 1805.

[19] 3rd Report, 1807.

[20] 8th Report, 1817.

[21] 2nd Report, 1805

[22] 2nd Report, 1805

[23] 3rd Report, 1807.

[24] National Records of Scotland, GD253/175/6. Offers by contractors for building bridges on the Inverfarigaig road addressed to joseph Mitchell 1830,

[25] The act of parliament which allowed for this can be found here https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/Geo3/44/75/pdfs/ukla_18040075_en.pdf

[26] 3rd Report, p63, 1807.

[27] National Records of Scotland. GD253/168/7. Draft contract for Inverfarigaig road and bridges. 1807. (Note some farm names are difficult to read and may not be correct)

[28] 4th Report April 1809.

[29] 10/2/1809, Inverness Journal. Held by Inverness central library.

[30] National Records of Scotland. GD253/168/7. Draft contract for Inverfarigaig road and bridges. 1807.

[31] Letter from Simon Fraser and John Mackintosh to Mr Rickman, 16/5/1810. National records of Scotland. GD253/168/8.

[32] 5th Report, April 1811

[33] 6th Report, Feb 1813

[34] 8th report, 1817

[35] 2nd Report, June 1805

[36] Letter from Simon Fraser and John Mackintosh to Mr Rickman, 16/5/1810. National records of Scotland. GD253/168/8.

[37] https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=15.0&lat=57.35067&lon=-4.20986&layers=205&b=1&o=100

[38] Report 14,1828, p50

[39] 6th Report, Feb 1813

[40] 6th Report, Feb 1813

[41] https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=14.0&lat=57.35545&lon=-4.21376&layers=205&b=1&o=100

[42] https://maps.nls.uk/geo/explore/#zoom=16.9&lat=57.34975&lon=-4.20434&layers=257&b=1&o=100

[43] Nairne, D. Memorable Floods in the Highlands during the Nineteenth Century With Some Accounts of the Great Frost of 1895. 1895

[44] 8th report, 1817.

[45] 5th Report for the Repair of roads and bridges 1819.

[46] 11th Report for the repair of roads and bridges, 1825.

[47] https://scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/digital-volumes/ordnance-survey-name-books/inverness-shire-os-name-books-1876-1878/inverness-shire-mainland-volume-20/13

[48] 16th Report of the Commissioners for the Repair of roads and bridges in Scotland. 25/3/1830. p7.

[49] Draft Contract for rebuilding bridges at Dunmaglass and Redburn on the Inverfarigaig road. NRS 253/175/2. 1830.

[50] Highland Roads and Bridges: Offers by contractors for building bridges on the Inverfarigaig road addressed to Joseph Mitchell. NRS 253/175/6. 1830.

[51] 4th Report, 1809

[52] 5th Report 1811

[53] 6th Report of the Commissioners for roads and bridges in the highlands of Scotland. 1813

[54] Letter from Simon Fraser and John Mackintosh to Mr Rickman, 16/5/1810. National records of Scotland. GD253/168/8

[55] Draft contract for rebuilding bridges at Dumnaglass and Redburn on the Inverfarigaig road. 1830. National Records of Scotland GD253/175/2

[56] Lauder, T.D. An Account of the Great Floods of August 1829 in the Province of Moray and adjoining districts. 1830.

[57] https://restorerivers.eu/wiki/index.php?title=Case_study%3AUpper_River_Nairn_restoration_project

[58] 8th Report of the Commissioners for roads and bridges in the Highlands of Scotland. 19/4/1817. p6.